The pressures, desires, and horrors for women to embrace motherhood, and all its complexities, are brought to the fore in this compelling new musicalthat feels urgent in its message.

Ballad Lines, directed by Tania Azevedo, interweaves three generations of women, whose lives are told through Scottish, Irish and Appalachian ballads, each grappling with their own role in a world where they are struggling for acceptance and agency. In particular, the musical places emphasis on being a mother, whether willingly or not, critiquing the longstanding mistreatment of women expected to fulfil predetermined societal roles, as well as reconciling with the idea of continuing the family line, a notion referenced clearly through the broader metaphor of the ballads passed down, uniting women and communities across centuries.

Its story is sparked by a box handed down to Sarah (Frances McNamee), a queer woman now living in New York, who inherits a box of tapes from her estranged Aunt Betty (Rebecca Trehearn). From here, encouraged by her partner Alex (Sydney Sainté), Sarah gradually listens to more and more of her Aunt’s tapes, which take her through the stories of Sarah’s ancestors, Cait (Kirsty Findlay) and Jean (Yna Tresvalles), whose heartbreak and struggles are embodied in the traditional ballad songs Betty wants kept alive.

As a premise, it is an intriguing start. The subtle tweak of the sound production works effectively to make Trehearn’s voice sound as if it is coming from the tape, and immediately, it evokes questions regarding why these tapes were made and why they were sent to Sarah. As the musical unfolds, its plotting lands largely successfully in not just weaving the three narratives together, but pulling similarities across of three close to helping to reinforce the play’s comments about women’s sacrifices and struggles across a 400-year period.

It is an ambitious attempt, and one that sticks the landing. Although the harsh Scottish accent and archaic dialogue take a little while to get used to (aided by a handy glossary in the programme), the musical quickly immerses you into the stories of all three women, Sarah, Cait and Jean, primarily through its glorious songs, put together by Finn Anderson. The ballads are moving, riotous, powerful and poignant, and, crucially, pitch it right always at the right time, striking a successful balance between traditional sounding melodies and pieces fit for a contemporary setting.

McNamee’s Sarah and Sainté’s Alex’s relationship forms the centrepoint of the musical. As two queer women, their relationship is immediately grounded in, at least for Sarah, reconciling against being shunned by her family, hence her reluctance to listen to Betty’s tapes. While Sarah’s primary function initially is to catapult us into the historical narratives, the toll of these stories soon becomes clear on Sarah, who then faces relationship troubles of her own when she reveals her desire for children with Alex. It is this particular plotline that wobbles the performance slightly, albeit well performed by a strong McNamme and a brilliantly layered Alex developed by Sainté. It feels a little rushed in comparison to the other two stories, and takes over the narrative in an unbalanced second half that shakes the musical’s momentum slightly.

As women from Sarah’s ancestry, Kirsty Findlay (Cait) and Yna Tresvalles (Jean) are simply superb in bringing out the horrifying, haunting, yet in some moments defiant, experiences of both characters. Findlay’s portrayal of Cait, a woman desperate to escape pregnancy, haunted by terrifying visions, is powerful, with her character’s slow breakdown deeply troubling. Meanwhile, a century later, teenage Jean’s untimely pregnancy sees her attempt to travel to America, full of a youthful energy that is desperately foreboding, drawn out by Tresvalles, who threatens to steal the show with this exceptional individual display. Again, though, for both of these women, their plots are a little too rapidly concluded, and feel much better paced prior to, than post, the interval.

Rebecca Trehearn’s Betty is a neat touch as a narrator-style figure. Betty is a necessary tool to shoehorn us into the flashbacks, while Ally Kennard’s multiroling as numerous men that either wrong or support the various women is effective in reducing the male characters to side characters, still relevant in propelling some of the narrative but never fully stealing the spotlight, a necessary concept in this play about preserving and highlighting the female experience.

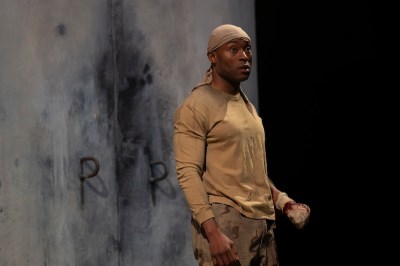

Ballad Lines is enhanced, too, by Tinovimbanashe Sibanda’s choreography. This is stark and frenetic, performed well by a cast whose energy reflects the chaos and inner turmoil of the musical’s characters. This is not a conventional musical, and the unconventional, angular choreography matches well. The production’s slick execution is furthered by TK Hay’s set design, which, dominated by wooden slat flooring, seamlessly transitions across the time periods and locations, perfect for quick switches not just in era but between stories too.

By its finale, Ballad Lines manages to reach a poignant, painful conclusion that refuses to tie everything up neatly like most musicals conventionally do. The complexity of its finale and the swathe of mixed emotions are effective in reiterating the piece’s wider ideas about womanhood and motherhood, and are defiant in establishing its new ballad for future generations to sing.

This is an ambitious, slick musical that, like the ballads it is inspired by, could run for generations.