You wait for one play about Mary Todd Lincoln and then two come along at once. This one, much less raucous and riotous than Broadway’s export ‘Oh Mary!’, presents the former First Lady as grief-stricken, on the verge of madness, and desperate to establish just who she is.

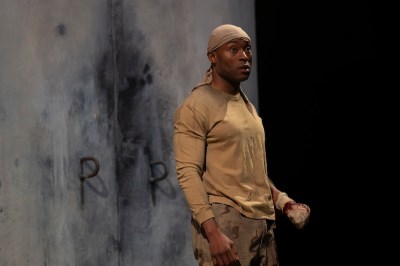

John Ransom Phillips’ script, which has undergone a little remodelling, places Mrs Lincoln (an electric Keala Settle) in the artistic studio of famous photographer Mathew Brady (Hal Fowler). There, Mary awaits her new portrait, which Brady confirms he will only take once he has found out what exactly Mary’s true self is. It is a conundrum that a grieving Mary is reckoning with herself, having lost a son in his infancy, her husband’s assassination and her eldest son wanting her institutionalised.

Phillips’ script blends rigid naturalism with eye-catching, vivid, abstract sequences. Brady quickly forms of Mary’s delusions, even going as far as appearing as an executioner, goading her into unthinkable actions. The switches from back and forth dialogue to stylised physical sequences and melodramatic multiroling from Fowler take a little time to get used to, but it is an effective way in revealing Mary’s complex persona, or, at least, how she is perceived by others. This is enhanced by Anna Kelsey’s careful set and costume design, maintaining a claustrophobic atmosphere in Brady’s studio, which, with dusky greens and dark furniture, enables Mary to be more fiercely illuminated and exposed.

As Mary, Settle shines as the formidable, complicated, former First Lady. It is a moving portrayal of a woman trapped in a purgatory, still alive while all around her, and dear to her, seems dead. Settle’s smirks, chuckles, and grimaces are subtle yet effective in demonstrating Mary’s longing for understanding her own identity, compounded by some decent physical routines choreographed by movement director Sam Rayner to fully capture the gradual, brutal exposure of Mary’s many ‘faces’.

Settle’s Mary is contrasted neatly by Fowler’s harsh, increasingly unsettling Brady. It is a little hard to work Brady out during the exposition, spouting numerous artistic metaphors in a way which stalls, rather than develops, the narrative, yet once he delves more deeply into Mary’s psyche, demanding to know what she really represents, he becomes a colder, nastier figure. Fowler’s multiroling is effective in enabling the episodic narrative to explore the various delusions and traumas that haunt Mary, with one particular sequence, towards the play’s conclusion, particularly harrowing.

That said, some of Branagh Lagan’s directorial choices feel a little jarring. While the incorporation of projection is very well done, with some great uses of lighting and digital reflections, often to generate the various portraits of Mary taken, the decision to depict Brady as some madcap scientist, almost Dr Frankenstein-esque, feels a step too far. Placing Brady in a red light room behind a scrim attempts to evoke him as processing his shots, but in essence, Fowler is asked to flail his arms, and compounded by a dark-lensed pair of spectacles seems too cartoonish to be true.

Nevertheless, it is through Settle’s terrific individual performance that this piece is at its most effective. Mary’s raw, unchecked, sense of grief is palpable, and Phillips’ script gives Mary her own chance to define our image of her, her legacy, rather than the male-oriented understanding history has given us, shrouding her in luxury and lunacy.

Like Mary, Mrs President is not perfect, but it is an ambitious and noble attempt to spotlight one of American history’s most infamous First Ladies.