Children’s stories from the devastating, devastated setting of Palestine are brought to the fore in this desperate, heartbreaking, verbatim production.

This disturbing, yet beautiful, solo show is brought to the stage using verbatim accounts taken fro Leila Boukarim and Asaf Luzon’s work, A Million Kites: Testimonies and Poems from the Children of Gaza, and centres upon 11-year-old Palestinian Renad, who desperately wants to be a storytelling when she grows up, finding comfort and hope in the stories she tells, when all hope around her seems to have disappeared. The production is produced by Good Chance, whose work includes the exceptional The Jungle, demonstrating a clear ability to stage compelling theatre about marginalised people.

It is a moving piece, performed superbly by Sarah Agha, who brings to the fore Renad’s childish mannerisms and excitement, contrasted with stunning, shocking brutality as the reality of living in a warzone starts to consume her everyday life. Agha’s energy as Renad is exceptional, utterly compelling over the hour-long performance. Yet, it is her multiroling, performing the verbatim lines of real Palestinian children, articulating their own experiences of living there, which punctuates the piece with gutwrenching vigour.

Renad spends much of the play looking for her family. The answer to this question of where they are is obvious to the audience, but Renad’s futile hope of being reunited with her loved ones, gone as victims of war, is brutal. This hope is spotlighted through Renad’s conversations with Anqaa, an ancient phoenix which represents a link between the harsh reality of Palestinian life and the beauty of Palestinian folklore. It is a beautiful image, projected frequently with fierce reds and oranges onto a cloth backdrop which mutates into something more violent, more haunting, as Renad’s awful existence unfolds.

Agha, oddly mic’d up, directed by Elias Matar, who also puts the piece together, brings the audience with her, taking us through bomb-stricken sanctuaries, in moments that evoke a sense of entrapment that no one, let alone someone so young, should have to endure. In essence, it is desperately sad, yet it is the horror of the stories, combined with the painful real-life accounts delivered by Agha, as well as the endless list of children’s names projected in a poignant finale, that reiterates the horrifying, young, human cost of this conflict.

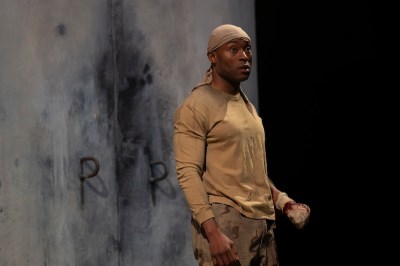

By its end, with Renad standing on a mound of sand, a simple set design by Natalie Pryce which resembles both the play areas Renad at her age should be at, and the sand-covered bomb craters she now exists in, it is impossible not to be moved by this image. Despite its brevity, A Grain of Sand forces audiences to reconcile with their own inaction while this suffering unfolds, with the unimaginable reality of life there, so painfully explored through verbatim accounts, made raw and visceral by Agha’s tremendous delivery.